Cell Division in Epithelial Tissue

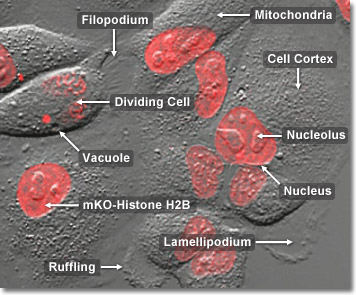

When observed through the microscope, the cell nucleus is well defined and surrounded by the nuclear envelope (or membrane) during interphase. Within the nuclear membrane are one or more nucleoli, which appear as spherical, dense structures when stained with fluorescent or absorbing dyes. On the outer periphery of the nucleus are two important organelles termed centrosomes, which were formed by duplication of a single copy during the last division cycle. Each centrosome contains a pair of centrioles that extrude visible microtubule networks through the cytoplasm in radial arrays, known as asters (derived from the term stars). Even though the chromosomes have been duplicated during the DNA synthesis (S) phase, individual chromatids are not visible in late interphase because the chromosomes still exist in the form of loosely packed chromatin fibers. In the digital video presented above, rabbit kidney (RK-13 line) epithelial cells labeled with the fluorescent protein, mKusabira Orange, fused to human histone H2B (orange-red nuclei) are observed undergoing mitosis using confocal illumination at 543 nanometers accompanied by differential interference contrast (DIC) in transmitted light.

Between mitotic divisions, a normal resting or actively growing cell exists in a state known as interphase, in which the chromatin forms a highly diffuse, fibrous network that is being continuously transcribed by enzymes within the nucleus. Before the cell enters the mitosis sequence, it first undergoes a DNA synthesis (or S) phase where each chromosome is duplicated to produce an identical pair of sister chromatids joined together by a specific DNA sequence known as a centromere. Centromeres are crucial to segregation of the daughter chromatids during mitosis. In the digital video presented above, rabbit kidney (RK-13 line) epithelial cells labeled with the fluorescent protein, mKusabira Orange, fused to human histone H2B (orange-red nuclei) are observed undergoing mitosis using confocal illumination at 543 nanometers accompanied by differential interference contrast (DIC) in transmitted light.

In order to ensure the inheritance of a complete ensemble of critical internal components by each daughter cell, the cell division process must provide for the segregation of organelles, such as mitochondria, the Golgi apparatus, and endoplasmic reticulum during mitosis. For example, the tubular, self-contained mitochondria are unable to assemble spontaneously from their component proteins, lipids, and enzymes, and can only be duplicated by growth and fission of pre-existing organelles. In a similar manner, the large interconnected membranous complexes of the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus require at least a portion of the original structure as a master template for duplication of the entire network. Segregation is accomplished by doubling the concentration of self-contained organelles (mitochondria) or by fragmentation, followed by vesicle formation, of the larger membrane-rich organelles (endoplasmic reticulum) during cell division. Vesicles of the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus appear to associate to some degree with the mitotic spindle, which is probably a mechanism designed to ensure even distribution between the daughter cells. In the digital video presented above, rabbit kidney (RK-13 line) epithelial cells labeled with the fluorescent protein, mKusabira Orange, fused to human histone H2B (orange-red nuclei) are observed undergoing mitosis using confocal illumination at 543 nanometers accompanied by differential interference contrast (DIC) in transmitted light.