|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

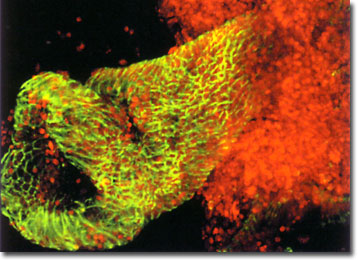

Confocal Microscopy Image Gallery

Human Colon Crypt

Double labeled with the fluorochromes Alexa Fluor 488 (green fluorescence) and To-Pro 3 (red fluorescence), the laser scanning confocal microscope image of a human colon crypt featured below reveals a significant amount of anatomical detail. The image was captured by Christine Anderson from the Ray White laboratory in the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah.

The colon is part of the vertebrate digestive system, extending from the cecum to the rectum in the large intestine. In humans, the primary functions of the colon are to lubricate and store waste products, as well as to absorb any residual salts and fluids from them. Similar to other hollow organs, the colon is composed of four layers: the mucosa epithelium, the submucosa, the muscalaris, and the adventitia or serosa. Extending throughout these multiple layers of the colon are simple tubular glands called crypts. Active stem cells located at the base of the crypts are responsible for renewing the intestinal epithelium, which is a dynamic tissue composed of several different types of cells.

Studies of the colon are important for their role in facilitating the attainment of basic anatomical information, as well their contribution to the understanding of various intestinal disorders. Confocal microscopy and fluorescent probes have benefited such studies by enabling the observation of thick specimens at high resolution, the marking of proteins and other colonic structures, and three-dimensional visualization of cells and tissues. Colon crypts, for example, are translucent and particularly amenable to fluorescent laser scanning confocal microscopy analysis. Their isolation and examination through this method has yielded significant information about crypt and pericryptal structural-functional relationships.